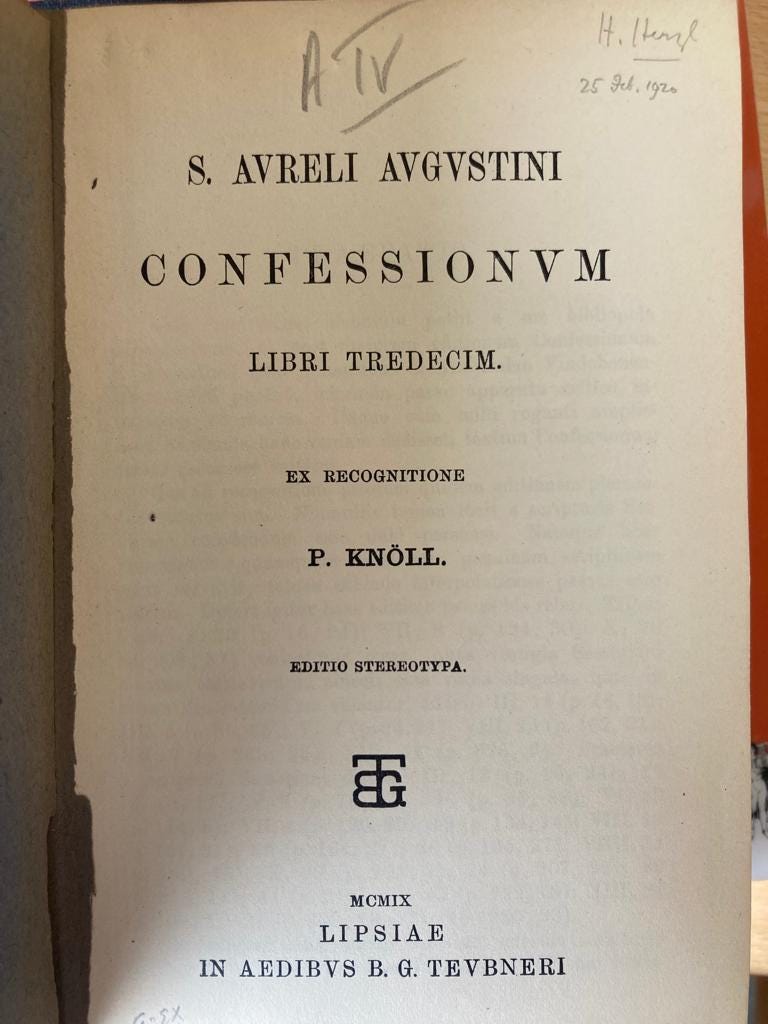

One night last summer I was sitting in my college library and writing a boring cover letter. I got stuck in the middle of a sentence and got up to pace in the stacks. At random my eye fell on a copy of St Augustine’s Confessions, a book I hadn’t read in a decade. I pulled it down. It was the 1907 Teubner edition, edited by Pius Knöll.

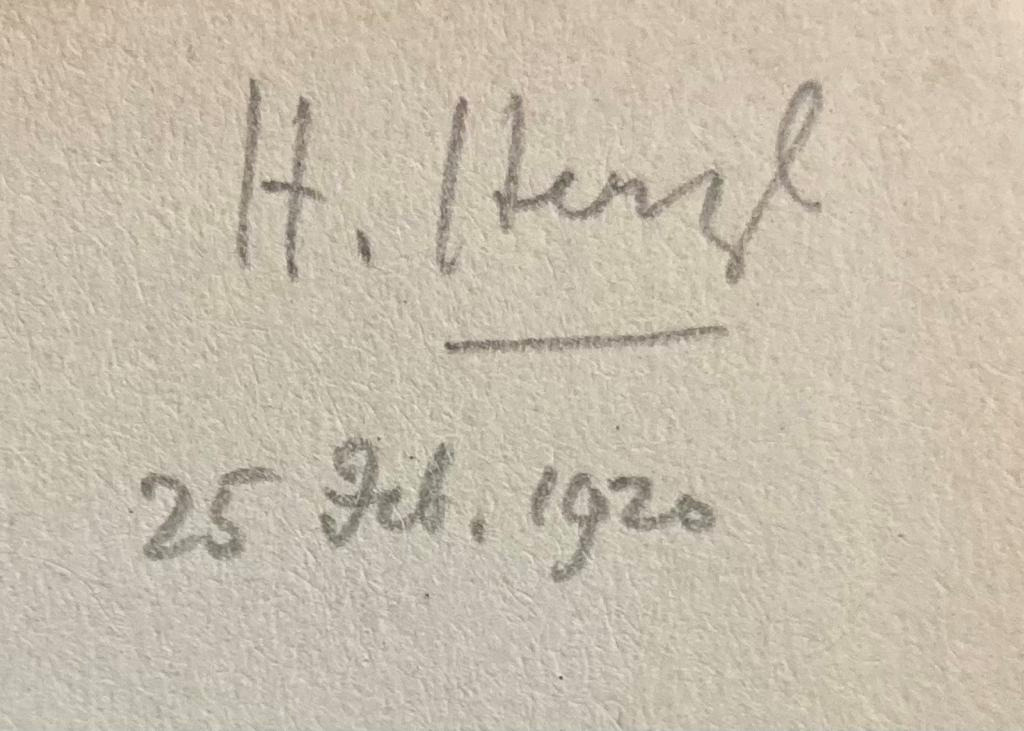

The signature at the top right of the page caught my eye:

There is no mistaking it: this book belonged to Hans Herzl (1891–1930), the only son of Theodor, the founder of Zionism. Hans Herzl had studied at St John’s College in Cambridge before the First World War, and the reader’s ticket is from a Cambridge bookshop. Nevertheless he signed the book in 1920 when, according to Ilse Sternberger,1 he was already in Vienna, so perhaps this book was put up for sale in Cambridge after his death, after which it found its way to Trinity Hall.

Hans had a sad life.2 He was born in Vienna and grew up in the shadow of his father, a man of gigantic worldwide fame. But Hans never married and never had any settled career, and spent his time shuffling from one European capital to another, translating the odd book from German into English.3 In 1923 he converted to Christianity, causing a minor scandal in the worldwide Jewish community. (He started as a Baptist and eventually became a Catholic.) Finally, in 1930 he felt he was going nowhere in life and killed himself, leaving behind a rather confused note urging Jews to Christianize their religion and Christians to be tolerant of Jews.

A couple of years later, Marcel Sternberger, who had written an article about Hans and was now preparing a book-length biography, wrote to Albert Einstein for commentary on Hans’s tragic conversion and death. This is the reply he got:

Dear Sir,

Your article about Hans Herzl made a great impression on me. His misspent life is a warning to all Jews against falling away from the community. For this reason, I regard the book you are writing as a worthy act for the Jewish cause.

Considering the strains on me I don’t think a personal meeting is in order. But I authorize you to make whatever use of the above remark that may be fit for winning attention for your book.

Here is the letter in its original German:

Now, Hans bought his copy of Augustine when he was first wrestling with the possibility of converting to Christianity. Ilse Sternberger (Marcel’s wife, who resumed the project he had left unfinished at his death) wrote the following footnoteless paragraph about this period in his life.

One Sunday, strolling through London’s Hyde Park he chanced upon a speaker from the Catholic Evidence Guild, a missionary society for the conversion of Jews, and found himself moved. He listened to its proponents from time to time, but did not seek them out. The idea instilled in him by his father and reinforced by Wolffsohn that only a cowardly Jew deserts his people was still powerful; besides, his infinite humility made him feel “unworthy to be a Christian.” But he started reading and rereading the New Testament as well as the Old with new awareness, and became more and more attracted to the image of the gentle Jesus in whose father’s house there were many mansions, and whose demands for blind faith touched a responsive chord in his soul.4

It turns out he read the Confessions as well as the Bible, or at least planned to. I can imagine it would have appealed to him, as the work of a fellow tormented lost soul. But on the other hand, Hans’s problem was quite unlike Augustine’s; it was not that he was a terrible sinner, but that he never had anything to do in his life. And neither the Confessions nor the Bible have very much to say to someone whose suffering comes from being at loose ends.

Ilse Sternberger, Princes without a Home: Modern Zionism and the Strange Fate of Theodore Herzl’s Children, 1900-1945 (San Francisco: International Scholars Publications, 1994).

See the following very well-researched online essay: https://simonmayers.com/2014/10/28/a-tale-of-religious-angst-and-self-deprecation-the-short-life-of-hans-herzl-1890-1930/

E. g. Oscar A. H. Schmitz, The Land Without Music, trans. H. Herzl (London: Jarrolds, 1925); Rochus, Baron von Rheinbaben, Stresemann: The Man and the Statesman, trans. Cyrus Brooks and Hans Herzl (New York: D. Appleton, 1929).

Princes without a Home, pp. 339–40.