The plural of octopus is octopi.

But you would never know this from a dictionary. In its first (1909) and second (1989) editions, the Oxford English Dictionary gave only the two options octopodes and octopuses. Curiously, it did not supply a single example of the supposed form octopodes, but apparently reasoned from some etymological principle that this was the correct pluralization of the word.

In its third edition (2004), the OED added the option octopi and made the following comment:

The plural form octopodes reflects the Greek plural. The more frequent plural form octopi arises from apprehension of the final -us of the word as the grammatical ending of Latin second declension nouns.

This comment is misleading in two respects. In the first place, there is no ‘Greek plural’ to speak of. As the OED itself notes, there was never any noun octopus in classical Greek, let alone in a plural form octopodes. Second, ‘apprehension’ implies that it is unlearned and illegitimate – but regretfully common, and therefore perhaps acceptable – to treat octopus as a Latin noun of the second declension. As we will see, there is absolutely nothing wrong with doing so.

It gets worse. Henry Fowler, author of the famous Dictionary of Modern English Usage, wrote under the entry Octopus that ‘the Greek or Latin plural, rarely used, is -podes, not -pi’. Under the entry Latin Plurals he also made the sneering comment:

In Latin plurals there are some traps for non-Latinists; the termination of the singular is no sure guide to that of the plural. Most Latin words in -us have plural in -i, but not all, & so zeal not according to knowledge issues in such oddities as hiati, octopi, & ignorami.

Gee, what an idiot you’d have to be to say octopi! And not only an idiot, but a vain idiot who pretends to know Latin.

The shamelessly titled Oxford Companion to the English Language is even more cocksure than Fowler was:

Purism, however, also has its barbarisms, such as the quasiclassical plurals octopi and syllabi for octopus and syllabus, competing with octopuses and syllabuses. (The Greek plurals for these words are, respectively, octṓpoda and sullabóntes [🚨 sic!!🚨 ].)

There’s no end to people who will smugly tell you that octopi is wrong. Wikipedia says that ‘The alternative plural "octopi" is considered grammatically incorrect because it wrongly assumes that octopus is a Latin second declension "-us" noun or adjective when, in either Greek or Latin, it is a third declension noun.’ This lady at Merriam Webster tells us that all pluralizations are right, from a certain point of view, but that octopi is grammatically shaky, that octopuses is normal, and that whereas octopodes is technically correct, it is strange and restricted to British English (?).

Well, I think we’ve had enough of experts saying that they know what the plural of octopus is and getting it consistently wrong. Octopodes is a preposterous hypercorrection, octopuses is fine but cumbersome, and octopi is correct.

Here goes. As the OED correctly points out, there is a class of Ancient Greek words in -πους that get pluralized as -ποδες. A good number of these words got Latinized in Antiquity, and the resulting Latin words ended in -us in the singular and -odes in the plural. Hence we have τρίπους-τρίποδες, which is tripus-tripodes in Latin. Some of these words eventually made it into English. If they did, their usual form is simply -pod, -pods. Thus we have tripod-tripods, tetrapod-tetrapods, sauropod-sauropods. But not a single one of these words has an English singular form in -us; that is, we don’t say tripus or tetrapus. Thus octopus is not in this lexical category, and is not to be compared to any of the words listed here. It might have been otherwise: we could easily have had the word octopod for the animal itself. (French, for instance, has octopode-octopodes.) But we don’t.

Then there is a class of native Latin words that end in -pes, and in the plural -pedes: for example, bipes-bipedes, pinnipes-pinnipedes, compes-compedes. There is even octipes-octipedes, ‘eight-footed’, which is attested by Propertius and Ovid; and multipes-multipedes, ‘many-footed’, which is in Pliny. Many of these words ended up in English, terminating either in -ped (if they came straight from Latin) or in -pede (if they were borrowed from an intermediate French form). It’s conceivable that we could have had the word octiped or octopede, just like we have biped and centipede. But again, we don’t.

The true analogy to octopus is a word which falls into a third class altogether: polypus. Since the proper English (and Latin) plural of polypus is polypi, the plural of octopus is accordingly octopi. Read on if you don’t take my word for it.

Polypus is a relatively common word in both Latin and Greek. As a (rare) Greek adjective it means ‘many-footed’, but in its first attestations in Greek it is already a noun, and denotes the tentaculate animal which we would now call an octopus. In one Linear B inscription, there is a reference to an object decorated by a painting of a po-ru-po-de, i.e. πωλυποδει.1 It also appears in Homer (Od. 5.432) as a third-declension noun in the form πουλύποδος. However, already by the sixth century BC the lyric poet Theognis wrote the verse:

Πουλύπου ὀργὴν ἴσχε πολυπλόκου, ὃς ποτὶ πέτρῃ

τῇ προσομιλήσῃ τοῖος ἰδεῖν ἐφάνη.

Make like the tangled octopus, who appears just like the rock he clings to.

…which implies the existence of a second-declension noun πούλυπος with nominative plural πούλυποι. From this point on, πουλύπους and πούλυπος existed as collateral forms (alongside some others), with respective plurals πουλύποδες and πούλυποι. By the third century AD, Athenaeus cited a profusion of verses that displayed both variants. (Incidentally, his whole discussion of literary octopi is exhaustive and interesting. It appears at Deipnosophistae 7.316a–318 f.) Athenaeus was very interested in the distinction between the accusative forms πουλύποδα and πουλύπουν, and also between the forms πώλυπος and πούλυπους. At no point did he address the specific question of the word’s belonging to the second declension, but he gave plenty of examples of that phenomenon. In short, the form polypodes did exist in Greek, but so did polypi. The word was indeed derived from πούς, ‘foot’, but it never occurred to anyone that it must necessarily be declined like πούς in isolation.

In Latin, the word was borrowed as pōlypus, and sorted into the second declension. (The Oxford Dictionary of Latin says that pōlypus comes from πουλύπους, but it would probably have been better to write πώλυπος, which is perfectly well attested and seems to be the real etymon.) Here the situation is unambiguous. Latin writers always understood the plural to be polypi, and never polypodes; a fact which is apparent from all the examples cited by Lewis & Short and the OLD. Here, for instance, is the word in Plautus:

Ubi manum inicit benigne, ibi onerat aliquam zamiam.

Ego istos novi polypos qui ubi quicquid tetigerunt tenent.

Whenever he lends a helping hand, he lays on some kind of damage. I know these polypi: whenever they touch something, they hold it fast.

– Aulularia 196–7

Now, pōlypus ended up in modern European languages in many variants. First there are Romance forms like poulpe, pieuvre, pulpo, and polpo, which represent the natural evolution of pōlypus in the spoken medieval languages. (Poulp exists even in English, apparently as a culinary term in recent usage.) Next, there are more learned medieval forms that preserve more of the original Latin word, whether as a name for an animal or else in the derived sense of ‘cancerous growth’. This category includes French polype, which was taken into English as polyp. Finally, there is the Renaissance revival polypus, which was grafted straight into modern languages from Latin. Just like in Latin, this word has the plural polypi in English, and is in ordinary medical use. Polypus, polypi: there are no two ways about it.

Keep this in mind as we turn to the modern word octopus. The first attestation that I can find of it in Latin is in De piscibus marinis, a 1554 treatise on fish by the French anatomist Guillaume Rondelet. He wrote:

ΠΟΛΎΠΟΥΣ et accusandi causa πολύποδα καὶ πολύπουν dixerunt Græci à pedum multitudine. Unde illi quoque qui Græciam nunc incolunt ὀκτόποδα vocant.

The ancient Greeks called this animal POLYPUS (in the accusative case, polypoda and polypun) on account of its many feet. For the same reason, the modern inhabitants of Greece call it octopus.2

Rondolet appears to have been mostly right about the modern Greeks: according to the Lexikon zur byzantinischen Gräzität, the word ὀκτάπους [sic] is attested in medieval Greek as a name for the modern octopus. I haven’t, however, been able to track down the sources cited in the LBG’s entry, so I don’t have a sense of how ὀκτάπους was generally declined. Luckily this question is of only the faintest importance. In any event, by the seventeenth century, Greeks were calling this animal ὀκτωπόδια, as the naturalist George Wheler observed.3

Two hundred years after Rondelet – in the early years of modern taxonomy – Carl Linnaeus’ student Fredrik Hasselquist wrote a description of Octopodia, an eight-legged kind of cuttlefish which he had seen in the harbour of Smyrna. According to him, ὀκτωπόδια was what the local Greeks called this creature.4

Carl Linnæus later adapted Hasselquist’s entry for the 1756 edition of his Systema naturæ, and applied the name Sepia octopodia to the set of animals that we now know as octopi. He also remarked that Rondelet had called this species Polypus octopus: not quite accurately, for as you can see from the citation above, Rondelet had merely said that the Greeks called a certain kind of polypus an ὀκτόπους.

In 1788, when Johann Friedrich Gmelin revised Linnaeus’ Systema naturæ for its thirteenth edition, he replaced Hasselquist’s coinage Sepia octopodia with Sepia octopus. Perhaps he thought that octopus was a more appropriate classical adjective than the puzzling octopodia. Or else he made a mistake. Or else his printer did. One way or another, this appears to have been the first modern taxonomic use of the word octopus.

In any case, Gmelin never meant octopus to be the standalone name of any animal. Octopus was rather an neo-Greek adjective which qualified a given animal as eight-footed, in this case a sepia. The neuter plural of it, meanwhile, was octopoda, which could be taken substantivally to denote the set of eightfooted molluscs. Similarly, Greek δίπους, ‘two-footed’, takes the neuter plural δίποδα, which means ‘bipedal animals’. Gmelin’s adjectival use of octopus is therefore a red herring, and does not correspond to modern English octopus. It has, however, come down to us as a taxonomic term. The order Octopoda, (or, if you prefer, the Octopods) comprises the eightfooted Cephalopods, which themselves make up a class within the phylum Mollusca.

It soon happened, however, that Gmelin’s adjective octopus became a noun in its own right, and then the common name of the animal itself. This is the source of our English word octopus. The first example of this usage that I can find is in a lecture by Henry Baker at the Royal Society in November 1758. He defined three kinds of ‘Sea Polypi’:

First, the Polypus, particularly so called, the Octopus, Preke, or Pour-contrel: to which our subject belongs. Secondly, The Sepia, or Cuttle-fish. Thirdly, the Loligo, or Calamary.5

For Baker, unlike for Gmelin, octopus was not merely a description of the number of feet that an animal had, but the name of a specific beast. Here we are no longer dealing with a Hellenizing adjective, but a substantive patterned directly after polypus.

The decisive step was taken in 1798, when Lamarck wrote a taxonomic reorganization of some molluscs.6 He distinguished four species of octopus: Octopus vulgaris, Octopus granulatus, Octopus cirrhosus, and Octopus moschatus. For Gmelin and Linnæus, octopus had been an adjective that specified a particular species of sepia or polypus. For Lamarck, however, octopus was the very name of the animal. It represented a genus which could be divided into species by the addition of disambiguating adjectives. Lamarck’s octopus was meant not to qualify, but to replace and supersede polypus.

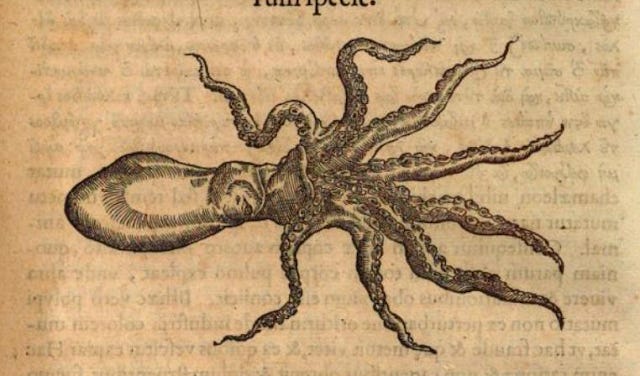

Drawings of Lamarck’s Octopus vulgaris.7

So it did. Over the century following Larmarck’s 1798 article, octopus displaced polypus as this animal’s common name in most European languages. Here are some examples from the OED:

The Octopus, which was the animal denominated Polypus by Aristotle, has eight arms of equal length. (1834)

The octopi also feed on conchyliferous mollusca. (1834)

The body of the octopus is small, it has legs sometimes a foot and a half in length, with about two hundred and forty suckers on each leg. (1835)

Help! The old magician clings like an octopus! (Robert Browning, 1880)

Young octopi, delicacy of the Japanese, hungrily searched about with their tentacles. (1942)

Now we have two words to distinguish from each other. There is octopus, the neo-Hellenistic adjective which Gmelin borrowed from Rondelet via Linnæus, and whose neuter plural substantival form, octopoda, begat English octopod(s). Then there is Lamarck’s octopus, a noun that denotes an animal in exactly the same manner as Latin polypus. I submit that as polypus only has one acceptable pluralization, polypi, only wanton pedantry could make us give its successor, the exactly analogous octopus, any other plural form than octopi.

We might even say that Octopods bears the same logical relationship to octopi as fishes does to fish, or louses to lice; in that the former refers to species of the same animal, and the latter to actual individuals. Examples of octopods are Octopus vulgaris and Enteroctopus dofleini. Examples of octopi are Pulpo Paul and Squidward Tentacles.

From a villa in Pompeii (1–2nd century AD).

Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, Documents in Mycenaean Greek (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1956), no. 246

Libri de Piscibus Marinis, in quibus veræ Piscium effigies expressæ sunt (Lyon: Matthias Bonhomme, 1554), p. 510.

A Journey into Greece (London: William Cademan, 1682), p. 291.

Fredrik Hasselquist, ‘Octopodia, Sepiæ Species’, Acta Societatis Regiæ Scientiarum Upsaliensis, 1751, pp. 33–35.

Henry Baker, ‘An Account of the Sea Polypus’, Philosophical Transactions, Giving Some Account of the Present Undertakings, Studies, and Labours, of the Ingenious, in Many Considerable Parts of the World vol. L, part II (1758): pp. 777–786 [778].

‘Extrait d’un Mémoire sur le genre de la Sèche, du Calmar et du Poulpe, vulgairement nommés, Polypes de mer’, Bulletin des sciences, par la Société Philomathique 1, no. 17 (Thermidor, an VI [July 1798]): pp. 129–131.

From Jean-Guillaume Bruguière, Tableau Encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la Nature. Contenant l’Helminthologie, ou les vers infusoires, les vers intestins, les vers mollusques, &c., vol. VII (Paris: Panckoucke, 1791), pl. 76.